Introduction to Piketty's Capital

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century (Harvard University Press 2014)

Patrick Toche

Introduction

- This set of slides surveys selected topics from Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a book written by economist Thomas Piketty, published in English in 2014 to great acclaim.

- All source files for this course are available for download by anyone without restrictions at https://github.com/ptoche/piketty

- The full course is expected to be completed by April 2015.

- The intended audience for these notes is any curious person with or without training in economics.

- The book deals with technical matters but its streamlined presentation of technical issues makes it highly readable.

Thomas Piketty

Capital in the 21st Century

- What do we know about the distribution of income?

- What do we know about the distribution of wealth?

- What prediction can we make about the evolution of income and wealth over the long term?

- Do the forces of private capital accumulation inevitably lead to the concentration of wealth in ever fewer hands?

- Can the balancing forces of growth, competition, and technological progress be strong enough to reduce inequality and reduce class conflicts?

- This introduction presents an ultra brief history of inequality and sketches the book's main themes.

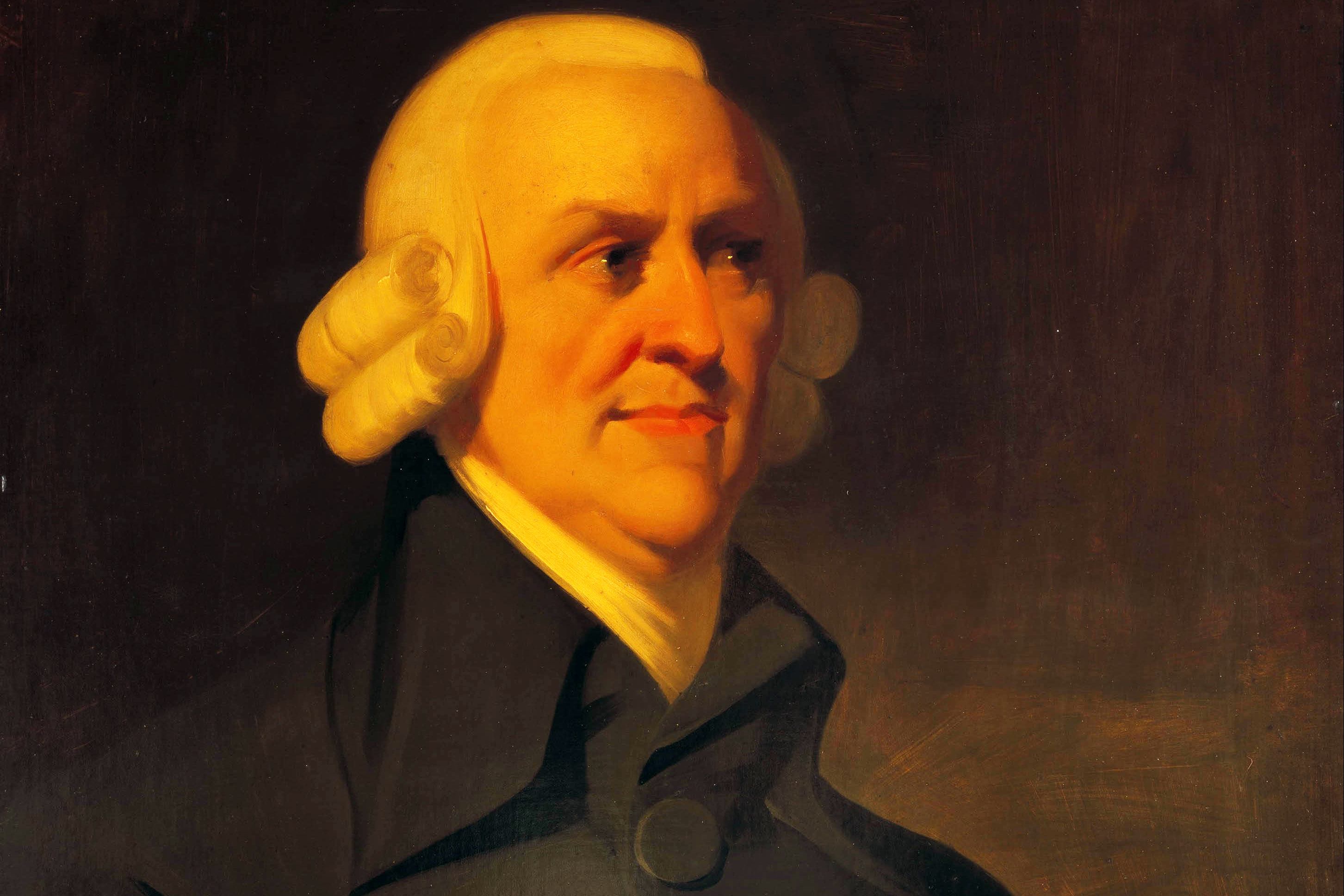

Adam Smith

Adam Smith and Poverty

- In 1776, Adam Smith published his study on the Wealth of Nations.

- Adam Smith is thought of as 'the first economist.' He lived in a world where poverty, hunger, and early death were commonplace. In this chaos he viewed the economy as nothing short of a miracle, the work of an 'invisible hand.'

- To Smith opulent societies are unequal and while backward societies are less unequal they are poor.

- Smith believed that capital accumulation would reduce the marginal productivity of capital and raise the marginal productivity of labor, helping to reduce equality.

- Smith expected that as the societies developed further, both equality and opulence would be achieved.

Thomas Robert Malthus

Malthus and the Problem of Overpopulation

- In 1798, Thomas Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population. His main fear was overpopulation.

- Population in the French kingdom had increased from 20 million in 1700 to 30 million by 1780. This very rapid population growth contributed to a stagnation of agricultural wages and an increase in land rents in the decades prior to the Revolution of 1789.

- As the country was getting richer, the poor were getting poorer, because there were more of them and the typical poor family's resources had fallen. This unfortunate paradox worried Malthus.

- Malthus argued that reproduction by the poor must be reduced to avoid overpopulation, chaos and misery, and that welfare assistance must be cut to achieve that.

David Ricardo

Ricardo and the Principle of Scarcity

- In 1817, Ricardo published his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. His main concern was the long-term evolution of land prices and land rents.

- Ricardo thought capitalism suffered from an internal contradiction.

- As both population and output grow steadily, land tends to become increasingly scarce relative to other goods. The law of supply and demand then implies that the price of land will rise continuously, as will the rents paid to landlords. The landlords will therefore claim a growing share of national income, at the expense of the rest of the population.

- For Ricardo, a politically acceptable solution was to impose a steadily increasing tax on land rents.

Ricardo and the Principle of Scarcity

- Ricardo's prediction proved wrong: the share of agriculture in national income decreased and the relative value of farm land declined.

- Ricardo had not anticipated the importance of technological progress and its role in offsetting the principle of scarcity.

- The principle of scarcity is still relevant: replace farmland with urban real estate and imagine what could happen to wealth inequality if the price trend of urban real estate 1970–2010 were extrapolated to 2010–2050!

- The mechanism of supply and demand eventually counterbalances extreme trends: If the supply of some good is short and its price too high, then demand for that good falls and its price eventually falls.

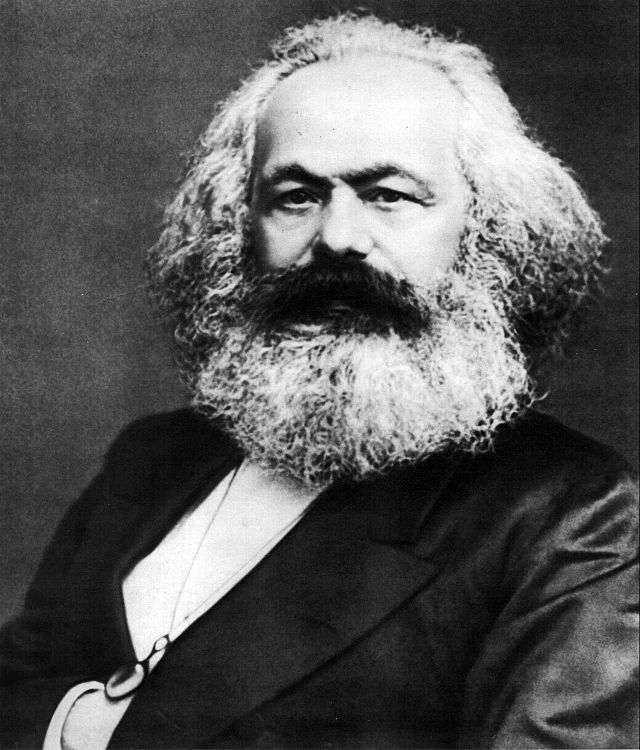

Karl Marx

Marx and the Kapital

- In 1867, Marx published the first volume of Capital. The other two volumes would be published posthumously by Friedrich Engels, the co-author of the Communist Manifesto (1848).

- The question was no longer whether farmers could feed a growing population or whether land prices would go on rising.

- During the first half of the 19th century wages stagnated at very low levels, in some cases even lower than previous centuries.

- The capital income share increased considerably in United Kingdom and France in the first half of the 19th century.

- With the industrial revolution and the vast rural exodus, workers crowded into urban slums. Poverty was now visible next to extreme opulence.

Marx and the Falling Rate of Profit

- Marx predicted a tendency for capitalists to accumulate wealth without limit and for wealth to become concentrated into ever fewer hands.

- Marx predicted the excessive accumulation of capital would lead to a falling rate of profit and the collapse of industrial capitalism.

- Marx saw the tendency of the profit rate to fall as 'the most important law of political economy.' As the rate of profit fell, capitalists would seek to extract more surplus and workers' wages would stagnate or fall.

- Marx's prediction proved wrong. In the last third of the nineteenth century, wages finally began to increase.

- The communist revolution took place in the most backward country in Europe, Russia, and not in the advanced industrial countries.

Simon Kuznets and the Kuznets Curve

- In 1953, Kuznets published Shares of Upper Income Groups in Income and Savings, a study of the United States over 1913–1948.

- Kuznets noted a sharp reduction in the upper deciles of income between 1913 and 1948. In 1913, the top 10% of US earners received 45–50% of annual national income. In 1948, they earned 30–35%.

- The 'Kuznets curve' interpretation is that inequality rises in the early stages of industrialization — falls later. An explanation is due to W. Arthur Lewis (1915-1991). In early stages, 'unlimited' supply of labour from rural areas allows urban areas to expand without upward pressure on wages. Wages rise once rural-urban migration stops.

- In truth, however, the compression of high incomes was largely accidental, caused by the Great Depression and World War II.

Piketty's Capital

- While Marx's vision was a nightmare, the Kuznets curve is a fairy tale.

- Piketty seeks to ground his theories on facts. He surveys economic data spanning several centuries and continents.

- Piketty's theory places the data within a simple, universal accounting framework and focuses on the very long run.

- Piketty's vision of the future draws from history and does not speculate about future technologies or future societies.

- This 'lack of imagination' leads Piketty to search for fiscal solutions to the economic and political problem of inequality.

- Piketty advocates high taxes on high incomes and wealth transmission.

Forces of Convergence & Divergence

- Convergence

- The main force is the diffusion of knowledge.

- depends on education policies, access to skills, institutions.

- Divergence

1.Top earners earn hundreds of times average earnings.2.Wealth concentration tends to occur when economic growth is smaller than the rate of return on wealth.- We have become accustomed to 1, thanks to the work of Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, and many others.

- We are now discovering 2 thanks to Piketty's book and the dire warnings of Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, and others.

Forces of Convergence & Divergence

- Figures I.1 and I.2 show two basic patterns of divergence.

- Figure I.1 depicts income inequality in the United States.

- Figure I.2 depict the capital/income ratio in 3 European countries.

- Both graphs depict "U-shaped curves": A period of decreasing inequality followed by one of increasing inequality.

- But the phenomena depicted in the figures involve distinct economic, social, and political processes.

Forces of Convergence & Divergence

- Figure I.1 shows the share of the upper decile of the income hierarchy in US national income from 1910 to 2010.

- The top decile claimed as much as 45–50% of national income in the 1910s–1920s, fell to 30–35% by the end of the 1940s, rose again in the 1980s, and by 2000 reached about 45–50%.

- Figure I.2 shows the total value of private wealth (real estate, financial assets, professional capital, net of debt) in the UK, France and Germany, expressed in years of national income, for 1870–2010.

- Private wealth was 600% to 700% of national income in the 19th century, fell to 200% or 300% in response to the shocks of 1914–1945 (wars and economic crises), rose steadily after 1950, and is up to about 500% today.

Income Inequality in the United States

- The spectacular increase in inequality largely reflects an unprecedented explosion of very elevated incomes from labor, caused by a separation of the top managers of large firms from the rest of the population.

- Did the skills and productivity of these top managers rise suddenly in relation to those of other workers?

- Do we live in a 'winner takes all' society?

- Top managers suddenly acquired the power to set their own remuneration. The 'winner grabs all' society!

- The tendency is less marked in other wealthy countries, but the trend is in the same direction.

The capital-income ratio

- The rise of capital/income ratios over the past few decades is in large part a return to a regime of slow growth.

- If the rate of return on capital remains above the growth rate for an extended period of time, then wealth becomes more concentrated.

- In slowly growing economies, past wealth matters more.

- The logic is captured by an inequality: \[ r > g \] where r stands for the average annual rate of return on capital, including profits, dividends, interest, rents, and other income from capital, and g stands for the rate of growth of the economy, that is, the annual proportional change in total income.